INSIGHT #1) Traumatic injuries, vascular abnormalities, cancer treatment and malfunctioning organs…traditionally, these involve loss of tissue or organ that could be restored only through surgical transfer from the patient and donor or through the use of synthetic materials. However, common challenges facing surgical care are that there is only so much tissue that can be removed from the same patient to reconstruct a damaged area. Also, the use of human or animal donor tissues have posed inherent risks of infection and graft failure.

INSIGHT #1) Traumatic injuries, vascular abnormalities, cancer treatment and malfunctioning organs…traditionally, these involve loss of tissue or organ that could be restored only through surgical transfer from the patient and donor or through the use of synthetic materials. However, common challenges facing surgical care are that there is only so much tissue that can be removed from the same patient to reconstruct a damaged area. Also, the use of human or animal donor tissues have posed inherent risks of infection and graft failure.

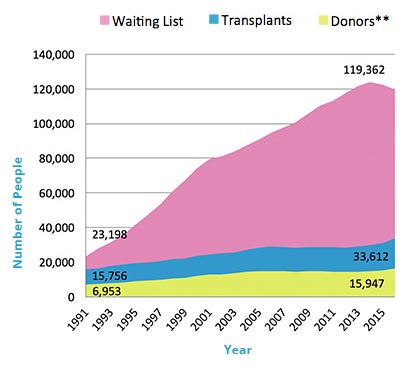

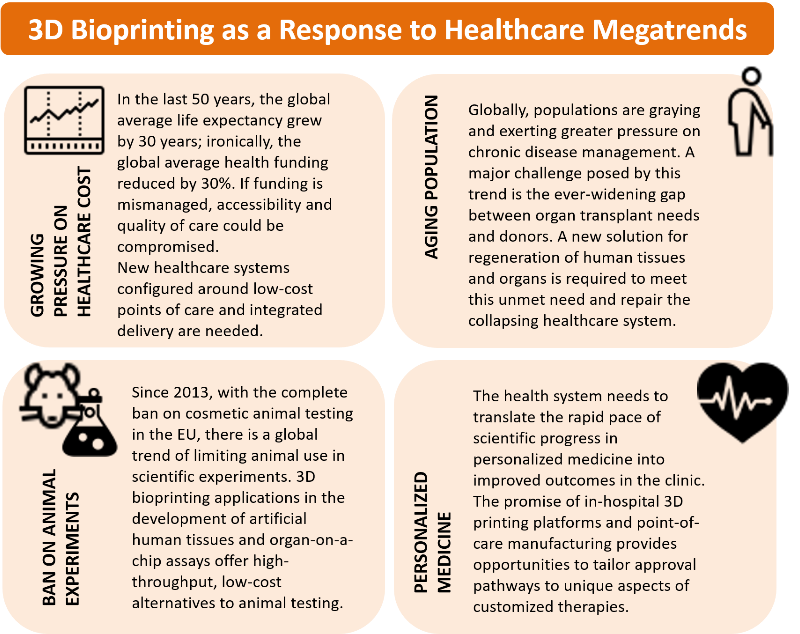

INSIGHT 2) But perhaps one of healthcare’s most profound problems, especially in the face of a globally aging population, is the sheer shortage of organ donors and rejection in existing transplantation methods. In 2016 in the U.S., around 116,000 were on the waitlist for an organ transplant while less than 10% of that number made up the donors list. Similar figures (respective to population size) are reported from other developed countries as in the EU; in less developed countries, the numbers on the waiting list are grossly masked by the numbers of people who pass away without even making it to the waitlist.

It is true that over the years post-transplantation 5-year survival rates have significantly improved (73% today versus 63% in 1980s for the heart) thanks to advances in immunosuppressive drug development. However, patients subjected to chronic regimens face new risks. From the risks of developing non-adherance to risks of developing antibodies to the biologics, post-allogeneic transplant management has its own concerns that can decrease quality of life and increase healthcare costs.

INSIGHT 3) There has been a rapidly growing attention to 3D printing in biomedicine in the past 5 years, both as a tool for tissue engineering research but also for clinical applications taking advantage of the unique benefits of personalized, automated printing of cells and biomaterials. The movement of the 3D bioprinting community is toward one vision – to generate organs and tissues on demand according to patients’ needs, using patients’ own cells.

In just a little over a decade since it was introduced to medical application, 3D printing has demonstrated its ability to revolutionize the delivery of health care across the world. Beyond the use in surgical prototyping and planning, 3D printing is being applied in fabricating constructs (medical devices or implants) with required structural, mechanical, and biological complexity that conventional methods lack in reproducing for patients. A 3D-printed bioresorbable airway splint saved a newborn’s life in the U.S.; a patient suffering with a degenerative cervical spine received a 3D-printed spinal implant recapitulating the complex internal architecture; a production of skin grafts clinically proven to treat burns was automatized with a 3D printer in Spain.